An anecdote about a costly missing comma in a telegram (told various ways) has been a favorite of teachers for years. It is employed to illustrate the effect that even as little as one lone punctuation mark can have on the meaning of a sentence and thus showcases an aspect of language studies often viewed as somewhat less vital than spelling and grammar. The tale is also called into service by those wishing to impress upon their young charges the importance of paying attention to detail:

The Price of a Comma

A woman touring Europe cabled her husband the following message: "Have found wonderful bracelet. Price seventy-five thousand dollars. May I buy it?"

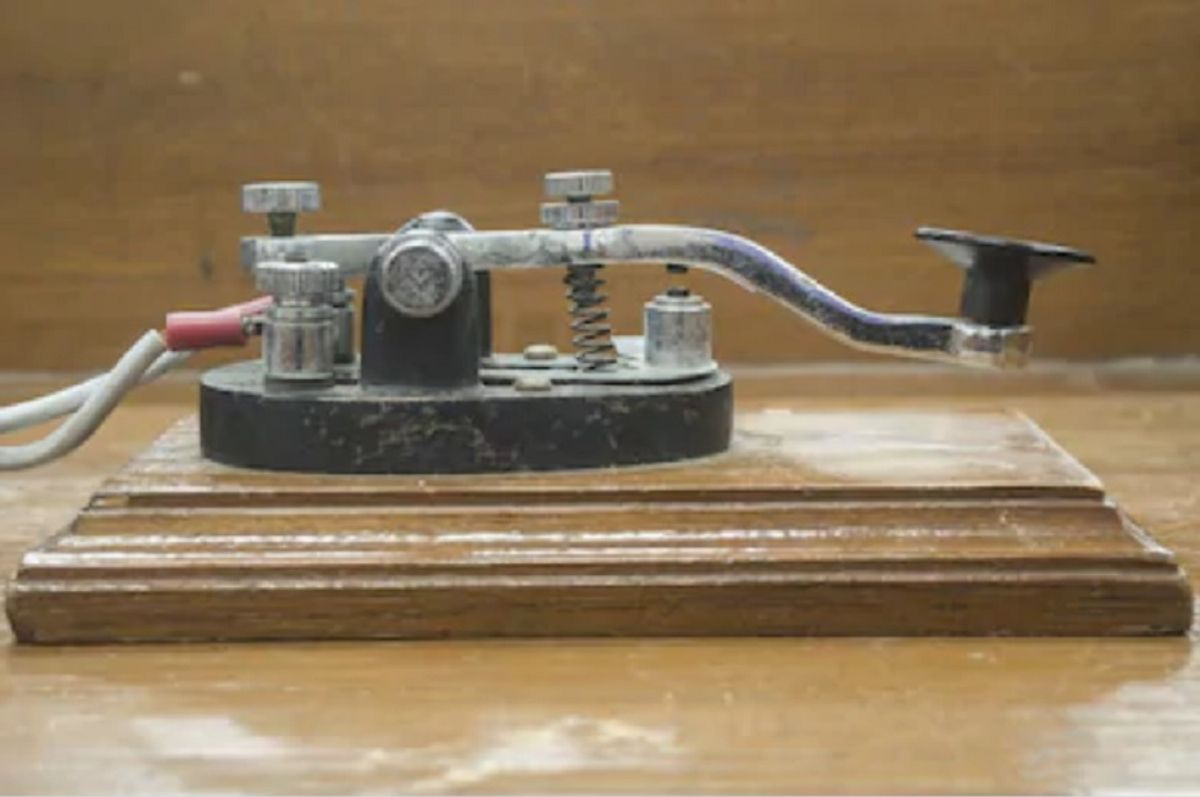

Her husband immediately responded with the message: "No, price too high." However, the telegraph operator missed one small detail in his transmission — the signal for a comma after the word "No."

The wife in Europe received the reply: "No price too high." Elated by the good news, she bought the bracelet. When she returned to the United States and showed the new bracelet to her shocked husband, he filed a lawsuit against the telegraph company — and won!

From that point on, telegraph rules required operators to spell out punctuation rather than use symbols. No price was too high to avoid the same mistake.

If there ever was such a lawsuit, we've yet to find evidence of it. Prior to 1937, telegraph companies did indeed spell out in full everything in the text of messages they transmitted, including punctuation marks (the most common example being the use of the word "STOP" to signify an end-of-sentence period), but this practice had to do with their bottom line profits in addition to a desire to convey the accurate meaning of communiqués rather than just their raw wordings. (In October 1937, the four major telegraph companies then operating in the U.S. — Western Union, RCA Communications, Postal Telegraph, and Mackay Radio and Telegraph — announced that they would no longer charge for the use of punctuation marks in domestic telegrams.)

Since punctuation marks were being spelled out, they were charged for as additional words, which meant it cost more to send telegrams with commas. Brevity is the soul of telegraphy, so whenever possible those who sent wires often edited their wordings down to messages that didn't require punctuation. The husband in the ersatz story, therefore, would probably have been better off all around if he had simply wired "PRICE TOO HIGH" rather than pay for the two additional words necessary to transmit "NO COMMA PRICE TOO HIGH."

The "No price too high" tale has been kicking about for at least a century. Consider this example harvested from a 1913 publication:

Another man, because of his inaccuracy lost a thousand dollars on a deal. A merchant in

San Francisco telegraphed to his correspondent in Sacramento: "Am offered ten thousand bushels of wheat on your account at one dollar a bushel. Shall I buy it, or is it too high?" The correspondent telegraphed back: "No price too high," instead of "No: price too high." Thus by leaving one little point out he lost one thousand dollars.

Other hoary yet much-loved tales communicate the same message about the importance of punctuation:

Alexander III personally wrote the death sentence of a prisoner with the following words: "Pardon impossible, to be sent to Siberia." His wife Dagmar (daughter of

Christian IX, king of Denmark) believed the man innocent. She saved his life by transposing the comma. The sentence then read: "Pardon, impossible to be sent to Siberia."

An English professor wrote the words, "Woman without her man is nothing" on the blackboard and directed his students to punctuate it correctly.

The men wrote: "Woman, without her man, is nothing."

The women wrote: "Woman: Without her, man is nothing."

In 1870s, the misuse of a comma in a tariff bill cost the U.S. about