Like impoverished people of other nationalities and ethnicities, many people emigrated from Ireland to the Americas in the 17th and 18th centuries as indentured servants; a smaller number were forcibly banished into indentured servitude during the period of the English Civil Wars; indentured servants often lived and worked under harsh conditions and were sometimes treated cruelly.

Unlike institutionalized chattel slavery, indentured servitude was neither hereditary nor lifelong; unlike Black slaves, white indentured servants had legal rights; unlike Black slaves, indentured servants weren't considered property.

A facet of U.S. history largely unfamiliar to Americans themselves is the role of indentured servitude in the survival and growth of the original 13 colonies. The earliest settlers needed laborers, but only wealthy people could afford passage to the New World. This led to a system whereby those who lacked means were brought from Europe under contract to work off their passage, room, and board over a period of two to seven years, until they were considered to have earned their freedom. No fewer than half of the immigrants who came to the New World during the colonial period arrived as indentured servants.

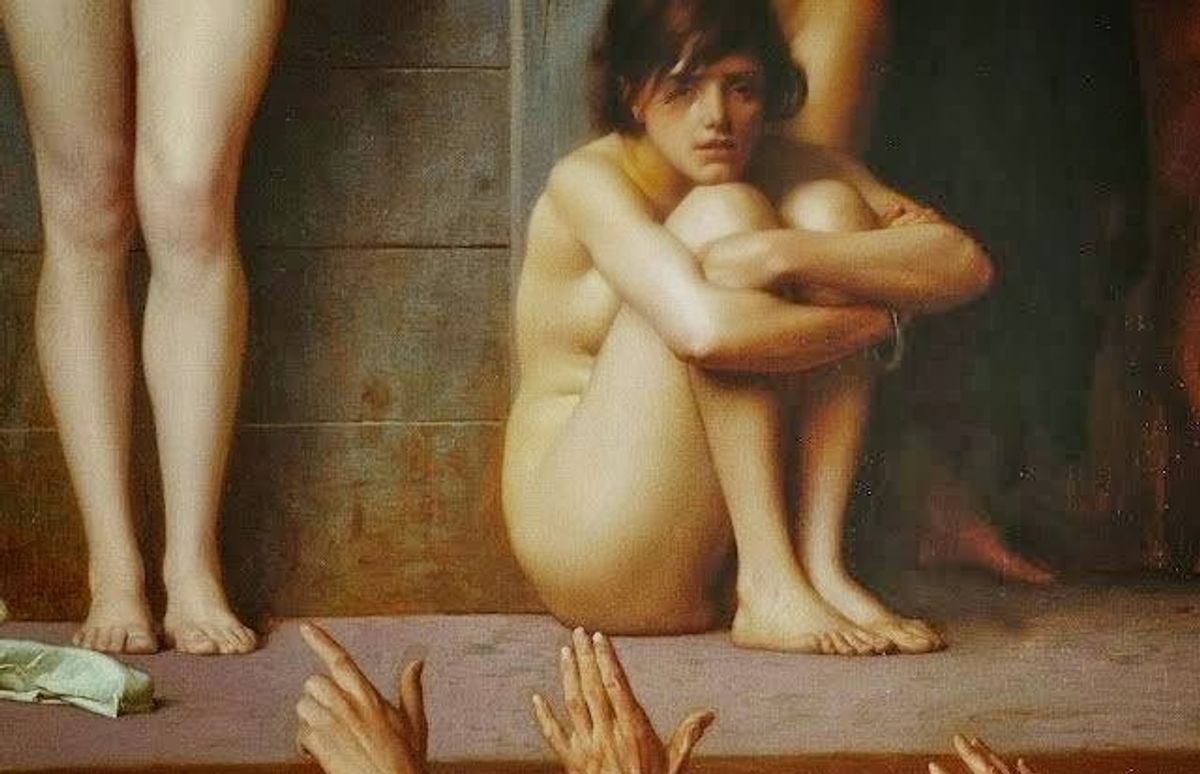

Among the many thousands of impoverished Europeans brought over in this fashion were men, women, and children from England, Ireland, Scotland, Germany, and elsewhere, but over the intervening centuries the notion has arisen that the Irish, in particular, were shipped to the New World as "white slaves."

In fact, according to an article first published on the internet in 2008 and endlessly recirculated since, Irish slaves were not only common in early America, they were more common than African slaves, and often treated more harshly. The article making these claims is usually credited to an individual named John Martin, who, in turn, found most of his "facts" in a 2003 article by James F. Cavanaugh called "Irish Slaves in the Caribbean." It has gone by many names, but as of mid-2016, the most shared version of the Irish slave narrative was entitled "Irish: The Forgotten White Slaves," and posted under the byline of a man named Ronald Dwyer.

Regardless of who is or isn't credited with writing it, nearly every iteration of the piece begins in exactly the same way:

They came as slaves: human cargo transported on British ships bound for the Americas. They were shipped by the hundreds of thousands and included men, women, and even the youngest of children.

Whenever they rebelled or even disobeyed an order, they were punished in the harshest ways. Slave owners would hang their human property by their hands and set their hands or feet on fire as one form of punishment. Some were burned alive and had their heads placed on pikes in the marketplace as a warning to other captives.

We don't really need to go through all of the gory details, do we? We know all too well the atrocities of the African slave trade.

But are we talking about African slavery? King James VI and Charles I also led a continued effort to enslave the Irish. Britain's Oliver Cromwell furthered this practice of dehumanizing one's next door neighbor.

The Irish slave trade began when James VI sold 30,000 Irish prisoners as slaves to the New World. His Proclamation of 1625 required Irish political prisoners be sent overseas and sold to English settlers in the West Indies.

By the mid 1600s, the Irish were the main slaves sold to Antigua and Montserrat. At that time, 70% of the total population of Montserrat were Irish slaves.

Ireland quickly became the biggest source of human livestock for English merchants. The majority of the early slaves to the New World were actually white.

From 1641 to 1652, over 500,000 Irish were killed by the English and another 300,000 were sold as slaves. Ireland's population fell from about 1,500,000 to 600,000 in one single decade. Families were ripped apart as the British did not allow Irish dads to take their wives and children with them across the Atlantic. This led to a helpless population of homeless women and children. Britain's solution was to auction them off as well.

Woven throughout is the implication that the reason so few Americans know anything about the so-called "forgotten" history of Irish slavery is that it has been excluded from "biased" history books.

Indentured Servitude vs. Chattel Slavery

Limerick-based research librarian and historian Liam Hogan takes aim at this notion in a series of papers debunking what he calls "the Irish slaves myth." There were no Irish slaves in the Americas, Hogan says. People who claim there were are conflating indentured servitude with chattel slavery — two distinct forms of servitude with more differences between them than similarities:

"White indentured servitude was so very different from black slavery as to be from another galaxy of human experience," as Donald Harman Akenson put it in If the Irish Ran the World: Montserrat, 1630-1730. How so? Chattel slavery was perpetual, a slave was only free once they they were no longer alive; it was hereditary, the children of slaves were the property of their owner; the status of chattel slave was designated by 'race', there was no escaping your bloodline; a chattel slave was treated like livestock, you could kill your slaves while applying "moderate correction" and the homicide law would not apply; the execution of 'insolent' slaves was encouraged in these slavocracies to deter insurrections and disobedience, and their owners were paid generous compensation for their 'loss'; an indentured servant could appeal to a court of law if they were mistreated, a slave had no recourse for justice.

The Race Factor

Hogan pins a 2014 resurgence of the Irish slaves narrative to increasing racial tensions within the United States, situating it within a larger world view desirous of absolving white Europeans of blame for the transatlantic slave trade that brought an estimated 12 million Africans to the New World in lifelong bondage:

From Stormfront.org, a self-described online community of white nationalists, to David Icke's February 2014 interview with Infowars.com, the narrative of the 'White slaves' is continuously promoted. The most influential book to claim that there was 'white slavery' in Colonial America was Michael Hoffman's They Were White and They Were Slaves: The Untold History of the Enslavement of Whites in Early America. Self-published in 1993, Hoffman, a Holocaust denier, unsurprisingly blames the Atlantic slave trade on the Jews. By blurring the lines between the different forms of unfree labour, these white supremacists seek to conceal the incontestable fact that these slavocracies were controlled by — and operated for the benefit of — white Europeans. This narrative, which exists almost exclusively in the United States, is essentially a form of nativism and racism masquerading as conspiracy theory.

That the institution of chattel slavery in America was founded on race is undeniable. Beginning in the late 1600s, the colonies all adopted "slave codes" which, among other things, routinely defined slaves as "Negro" or "African," according to the Encyclopedia Britannica:

In all of them the color line was firmly drawn, and any amount of African heritage established the race of a person as black, with little regard as to whether the person was slave or free. The status of the offspring followed that of the mother, so that the child of a free father and a slave mother was a slave. Slaves had few legal rights: in court their testimony was inadmissible in any litigation involving whites; they could make no contract, nor could they own property; even if attacked, they could not strike a white person.

The Dred Scott decision handed down by the Supreme Court in 1857 reaffirmed that racialized definition of slavery. The 7 to 2 decision in Scott v. Sanford held that plaintiff Dred Scott, a Black slave, did not qualify as an American citizen and had no standing to sue in federal court because, in part, persons imported as slaves "had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order":

In the opinion of the court, the legislation and histories of the times, and the language used in the Declaration of Independence, show, that neither the class of persons who had been imported as slaves, nor their descendants, whether they had become free or not, were then acknowledged as a part of the people, nor intended to be included in the general words used in that memorable instrument ... They had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations; and so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect; and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit.

Mistreatment of the Irish

In terms of historical accuracy, the Irish slave story is a hodgepodge. For example, the "Proclamation of 1625" supposedly requiring all Irish prisoners to be sent overseas did not exist. You won't find it in any history books. There was a 1603 proclamation by James I ordering that "rogues, vagabonds, idle, and dissolute persons" be "banished and conveyed" to "places and parts beyond the seas," etc., but this was not directed at the Irish in particular. It was put to use decades later in the wake of the English Civil Wars, however, as a justification for forcibly shipping thousands of Irish prisoners, vagrants, and orphans to the Caribbean as indentured servants. More than any other, this historical fact inspired the notion that the Irish were enslaved. Still, the text wildly exaggerates the number of those treated in this fashion, falsely claiming that "300,000 were sold as slaves." (Liam Hogan unravels these and similar statistical misrepresentations in "A Review of the Numbers in the Irish Slaves Meme.")

Words Matter

That thousands of Irish people were carried across the sea against their will and indentured to serve on plantations isn't disputed. It happened. What's in question is whether or not they are rightly referred to as "slaves." Some writers, such as genealogist and Irish Times columnist John Grenham, ask why not:

The labor they did was slave labor, and their circumstances were much worse than those of the indentured workers who traveled at the same time and later, not least because indentured work, though often harsh, was voluntary and time-limited. Refusing to call them slaves is quibbling.

Is it mere quibbling? Generically speaking, any form of forced labor can be called slavery. But what do we gain by doing so, besides blurring historical distinctions? Consider impressment, the 18th-century British naval practice of kidnapping young men and forcing them to serve on sailing vessels. That's slavery, in a sense. So is being sentenced to hard labor in prison. But while these share features in common with the institution of chattel slavery in America, they are on a whole separate plane.

It isn't "bias" that keeps legitimate historians from substituting the term "slavery" for "impressment," "hard labor," or even "forced indentured servitude." It's a simple respect for the facts.