Claim: Bags of rice sent to President Eisenhower helped dissuade him from launching an attack against China.

Example: [Collected on the Internet, 2003]

*** URGENT ACTION CAMPAIGN *** RICE FOR PEACE -- NO WAR ON IRAQ Visit: https://www.RiceForPeace.org/ Peace activists across the country are participating in a new method of democracy - sending more to their politicians than a letter. In the 1950's, tens of thousands of people sent small bags of grain to President This will only take a small about of time, but the cumulative effect of thousands of people doing this could be enormous. Our message to Bush is that if we are going to send something to Iraq, it should be food, not bombs. It should be peace, not war. SEND A HALF-CUP OF UNCOOKED RICE with the message: "Rice for Peace - No War On Iraq" on the OUTSIDE of the package. Rice MUST be packaged in a "burped" plastic bag and sent in a strong padded ENVELOPE or box — we DO NOT want to create a problem for U.S. and White House postal workers. Please use your correct return address and be sure to affix sufficient postage. Mail to: President George Bush E-mail your city and state to RiceForPeace@indra.com so your contribution to this peace effort is counted! Thanks for your participation! Please send this to your e-mail lists. Copy and paste it into a new This amazing idea from the Boulder Mennonite Church: There is a grassroots campaign underway to protest war in Iraq in a simple, but potentially powerful way. Place 1/2 cup uncooked rice in a small plastic bag (a snack-size bag or sandwich bag work fine). Squeeze out excess air and seal the bag. Wrap it in a piece of paper on which you have written, "If your enemies are hungry, feed them. Place the paper and bag of rice in an envelope (either a letter-sized or padded mailing envelope-both are the same cost to mail) and address them to: President George Bush White House, Attach $1.06 in postage. (Three 37-cent stamps equal $1.11.) Drop this in the mail. It is important to act NOW - TODAY so that President Bush gets the letters ASAP, especially since the inspector's report comes out on the 27th. In order for this protest to be effective, there must be hundreds of thousands of such rice deliveries to the White House. We can do this if you each forward this message to your friends and family. There is a positive history of this protest! In the 1950s, Fellowship of Reconciliation began a similar protest, which is credited with influencing President Eisenhower against attacking China. Read on: "In the mid-1950s, the pacifist Fellowship of Reconciliation, learning of famine in the Chinese mainland, launched a 'Feed Thine Enemy' campaign. Members and friends mailed thousands of little bags of rice to the White House with a tag quote in the Bible, 'If thine enemy hunger, feed him.' As far as anyone knew for more than ten years, the campaign was an abject failure. The President did not acknowledge receipt of the bags publicly; certainly, no rice was ever sent to China. "What nonviolent activists only learned a decade later was that the campaign played a significant, perhaps even determining role in preventing nuclear war. Twice while the campaign was on, President Eisenhower met with the Joint Chiefs of Staff to consider U.S. options in the conflict with China over two islands, Quemoy and Matsu. The generals twice recommended the use of nuclear weapons. President Eisenhower each time turned to his aide and asked how many little bags of rice had come in. When told they numbered in the tens of thousands, Eisenhower told the generals that as long as so many Americans were expressing active interest in having the U.S. feed the Chinese, he certainly wasn't going to consider using nuclear weapons against them." |

Origins: The

"Rice for Peace" campaign is real in the sense that it is a genuine grass roots effort, organized by Stirling Cousins of the Rocky Mountain Peace and Justice Center. As the Boulder Daily Camera reported:

"The idea is to inundate him with these packages of rice so he gets the idea that we don't want a war," she said. "It's something people can do to personally send a message about what they want. If we're going to send something to Iraq, it should be food, supplies and peace negotiations, not bombs." Cousins said the response so far has been strong, and she expects the number of bags the White House receives to be in the tens of thousands.

Stirling Cousins of the Rocky Mountain Peace and Justice Center organized the Rice for Peace campaign as a grassroots effort to urge President Bush to avoid war with Iraq. Cousins sent

Although the current "Rice for Peace" campaign is a sincere effort aimed at heading off a war between the USA and Iraq, the premise on which it is based is false. The anecdote reproduced above, about the Fellowship of Reconciliation's (FOR) waging a similar campaign in the 1950's which supposedly influenced President Eisenhower's decision not to wage (nuclear) war against China during the political crises over the islands of Quemoy and Matsu in

There was a famine in China, extremely grave. We urged people to send President Eisenhower small sacks of grain with the message, 'If thine enemy hunger, feed him. Send surplus food to China.' The surplus food, in fact, was never sent. On the surface, the project was an utter failure. But then - quite by accident - we learned from someone on Eisenhower's press staff that our campaign was discussed at three separate cabinet meetings. Also discussed at each of these meetings was a recommendation from the Joint Chiefs of Staff that the United States bomb mainland China in response to the Quemoy-Matsu crisis. At the third meeting the president turned to a cabinet member responsible for the Food for Peace program and asked, 'How many of those grain bags have come in?' The answer was 45,000, plus tens of thousands of letters. Eisenhower's response was that if that many Americans were trying to find a conciliatory solution with China, it wasn't the time to bomb China. The proposal was vetoed

Do you remember FOR's campaign in '54 and '55? There's a story we haven't told very often because it was told to us in great confidence — but that was nearly twenty years ago.

While this interview does provide an identifiable source for the information, it is also a single, unverifiable, third-hand account obtained from an anonymous source and not disclosed until twenty years after the fact, and as such its probative value is quite marginal. The anecdote as given appears to be a garbled account of a 1954 effort undertaken by the Fellowship of Reconciliation to have small bags of wheat (not rice) sent to the White House for the purpose of prompting the Eisenhower administration to undertake relief efforts on behalf of China, where a catastrophic flood on the Yangtze River had left thousands homeless and hungry. Nothing in contemporary news accounts of the 1955 'Feed Thine Enemy' effort mentions the campaign's being tied to an anti-war cause — the issue was that since China had declined aid from international relief organizations (such as the Red Cross) and would not allow private voluntary organizations from the "free world" into the country to supervise the distribution of food and other supplies, the Fellowship of Reconciliation's director felt that the

As The New York Times reported in March 1955:

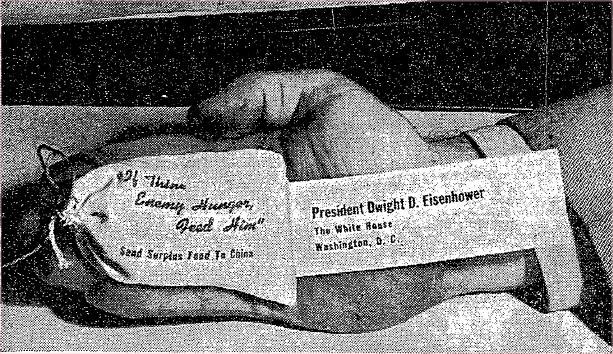

This time it is hundreds of bags of wheat. They are tiny bags, weighing about two ounces, and are addressed to President Eisenhower at the White House. The bags carry the inscription: "If Thine Enemy Hunger, Feed Him." In smaller letters are the words: "Send Surplus Food to China." The bags are being mailed to the White House from all over the country. They come from citizens who have responded to the appeal of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, 21 Audubon Avenue, Manhattan. This organization started its drive for the Administration to heed The Fellowship['s director, Alfred Hassler] stated that an offer "with no political strings attached" would be hard for the Peiping Government to refuse. The organization also said that distribution should be left to the Chinese Government "even though we might feel that we could do it better, and even though we fear that some food might be diverted to other ends." "Part of the world problem America faces is the suspicion on the part of Asians and others that we think we can do everything better than they," the fellowship said. That the Red Chinese Government had not asked for aid is "hardly significant," Mr. Hassler wrote. "On the other hand," he said, "the fact that the United States has offered help freely to 'friendly' nations stricken by similar disasters but not to China, is significant."

The Administration has another wheat problem.

WHEAT SENT TO WHITE HOUSE: One of tiny bags of wheat mailed by citizens at urging of a group that is campaigning for the sending of surplus U.S. food to the Chinese.

Herbert L. Pankratz, a helpful archivist at the

The Fellowship of Reconciliation was an organization of religious pacifists whose leaders and members contacted the White House on numerous occasions advocating giving food to the USSR, opposing military aid to Pakistan, favoring clemency for the Rosenbergs, opposing the rearming of West Germany, urging clemency for Communists convicted under the Smith Act, opposing nuclear tests in the Pacific, favoring clemency for Japanese war criminals, and opposing the sending of spy planes over Russia. This organization had also supported efforts of the U.S. Government to send food aid to East Germany and Hungary. In 1954 China suffered major flooding along the Yangtze River in some of its key rice-growing areas. Life magazine There is no indication in our files or in the New York Times article that this food for China campaign was intended as a protest against the possibility of the U.S. going to war with Communist China. It appears There is a small note in the file on the Fellowship of Reconciliation which indicates that it was considered a "subversive" organization. A lot of the correspondence from its leaders to the President was referred to Communist Chinese forces threatened the Nationalist-held island of Quemoy and Matsu on two occasions, September 1954-March 1955 and August-September 1958. During both of these crises various military and civilian advisers advocated the use of atomic weapons if war broke out and the U.S. had to intervene. President Eisenhower, while acknowledging the fact that the U.S. would need to use the ultimate weapon if full-scale war with China occurred, indicated that Congress and our allies would have to be consulted first. He continued to work for peaceful solutions which would avoid U.S. involvlement in an Asian war. We have checked summaries of discussion and memoranda of conversation for various meetings Eisenhower had with military advisers and the National Security Council and have found no references to the bags of wheat or food for China campaign. There is no documentation in our files to support the story that the bags of wheat influenced Eisenhower's decisions during the Formosa Straits crisis. The documents reveal that Eisenhower made his decisions based on his understanding of the strategic and diplomatic considerations as well as on intelligence reports and military options. An account of Eisenhower's handling of the Formosa Straits crises can be found in the book, Eisenhower: The President by Stephen E. Ambrose (Simon and Schuster, 1984).

Report re the Fellowship of Reconciliation Food for China Campaign and the Formosa Straits Crises of 1954-55 and 1958

weighing about

Administration for a response. F.O.A. Administrator Harold Stassen noted that they had sent out over 4,500 such responses. The letters to individuals who had sent in a bag of wheat reminded them of some Cold War realities. The International Red Cross had offered assistance to China but had been turned down. In addition, the Chinese government was continuing to export food to the Soviet Union and other countries to fulfill trade agreements while their own people suffered.

that it was strictly a humanitarian effort.

the Protective Research Section of the Secret Service. With this classification, justified or not, there is virtually no likelihood that the President would have paid any attention to any bags of wheat or letters sent in by this organization or its members.

The account of the Formosa Strait crises provided in the aforementioned book (by historian Stephen Ambrose) makes it clear that Eisenhower never had any intention of "bombing mainland China" or launching a pre-emptive nuclear strike against the Communist Chinese; no "Food for China" campaign could possibly have been instrumental in dissuading him against choosing options he was never considering in the first place. Moreover, it's simply wrong to assert that a "Food for China" campaign prompted Eisenhower to decide that "he certainly wasn't going to consider using nuclear weapons against [the Chinese]," as he had already publicly stated that he most definitely would use them if the Communist Chinese invaded Quemoy and Matsu:

At Eisenhower's March 16 [1955] news conference, Charles von Fremd of CBS asked him to comment on [Secretary of State] Dulles' assertion that in the event of war in the Far East, "we would probably want to make use of some tactical nuclear weapons." Eisenhower was unusually direct in his answer: "Yes, of course they would be used." He explained, "In any combat where these things can be used on strictly military targets and for strictly military purposes, I see no reason why they shouldn't be used just exactly as you would use a bullet or anything else."

Even if Eisenhower were aware of the "Food for China" campaign, and even if he made the comment attributed to him (which might have been offered in jest, for all we know), it would be a very large stretch of the truth to claim that his decision-making was influenced by

Additional Information: Last updated: 5 January 2008

Eisenhower's handling of the Quemoy-Matsu crisis was a tour de force, one of the great triumphs of his long career. The key to his success was his deliberate ambiguity and deception. As Robert Devine writes, "The beauty of Eisenhower's policy is that to this day no one can be sure whether or not he would have responded militarily to an invasion of the offshore islands, and whether he would have used nuclear weapons." The full truth is that Eisenhower himself did not know. In retrospect, what stands out about Eisenhower's crisis management is that at every stage he kept his options open. Flexibility was one of his chief characteristics as Supreme Commander in World

![]()

Rice for Peace: Origin of the Idea in 1954 (Fellowship of Reconciliation)

Sources:

Sources:

Article Tags