In August 2019, as many people took to the Internet to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment, which gave women the right to vote on paper, a piece of text started to circulate on social media that supposedly listed "9 things that women couldn't do until 1971":

The following list is of NINE things a woman couldn't do in 1971 – yes the date is correct, 1971.

In 1971 a woman could not:

1. Get a Credit Card in her own name – it wasn't until 1974 that a law forced credit card companies to issue cards to women without their husband's signature.

2. Be guaranteed that they wouldn't be unceremoniously fired for the offense of getting pregnant – that changed with the Pregnancy Discrimination Act of *1978*!

3. Serve on a jury - It varied by state (Utah deemed women fit for jury duty way back in 1879), but the main reason women were kept out of jury pools was that they were considered the center of the home, which was their primary responsibility as caregivers. They were also thought to be too fragile to hear the grisly details of crimes and too sympathetic by nature to be able to remain objective about those accused of offenses. In 1961, the Supreme Court unanimously upheld a Florida law that exempted women from serving on juries. It wasn't until 1973 that women could serve on juries in all 50 states.

4. Fight on the front lines – admitted into military academies in 1976 it wasn't until 2013 that the military ban on women in combat was lifted. Prior to 1973 women were only allowed in the military as nurses or support staff.

5. Get an Ivy League education - Yale and Princeton didn't accept female students until 1969. Harvard didn't admit women until 1977 (when it merged with the all-female Radcliffe College). Brown (which merged with women's college Pembroke), Dartmouth and Columbia did not offer admission to women until 1971, 1972 and 1981, respectively. Other case-specific instances allowed some women to take certain classes at Ivy League institutions (such as Barnard women taking classes at Columbia), but, by and large, women in the '60s who harbored Ivy League dreams had to put them on hold.

6. Take legal action against workplace sexual harassment. Indeed the first time a court recognized office sexual harassment as grounds for any legal action was in 1977!

7. Decide not to have sex if their husband wanted to – spousal rape wasn't criminalized in all 50 states until 1993. Read that again ... 1993.

8. Obtain health insurance at the same monetary rate as a man. Sex discrimination wasn't outlawed in health insurance until 2010 and today many, including sitting elected officials at the Federal level, feel women don't mind paying a little more. Again, that date was 2010.

9. The birth control pill: Issues like reproductive freedom and a woman's right to decide when and whether to have children were only just beginning to be openly discussed in the 1960s. In 1957, the FDA approved of the birth control pill but only for "severe menstrual distress." In 1960, the pill was approved for use as a contraceptive. Even so, the pill was illegal in some states and could be prescribed only to married women for purposes of family planning, and not all pharmacies stocked it. Some of those opposed said oral contraceptives were "immoral, promoted prostitution and were tantamount to abortion." It wasn't until several years later that birth control was approved for use by all women, regardless of marital status. In short, birth control meant a woman could complete her education, enter the work force and plan her own life.

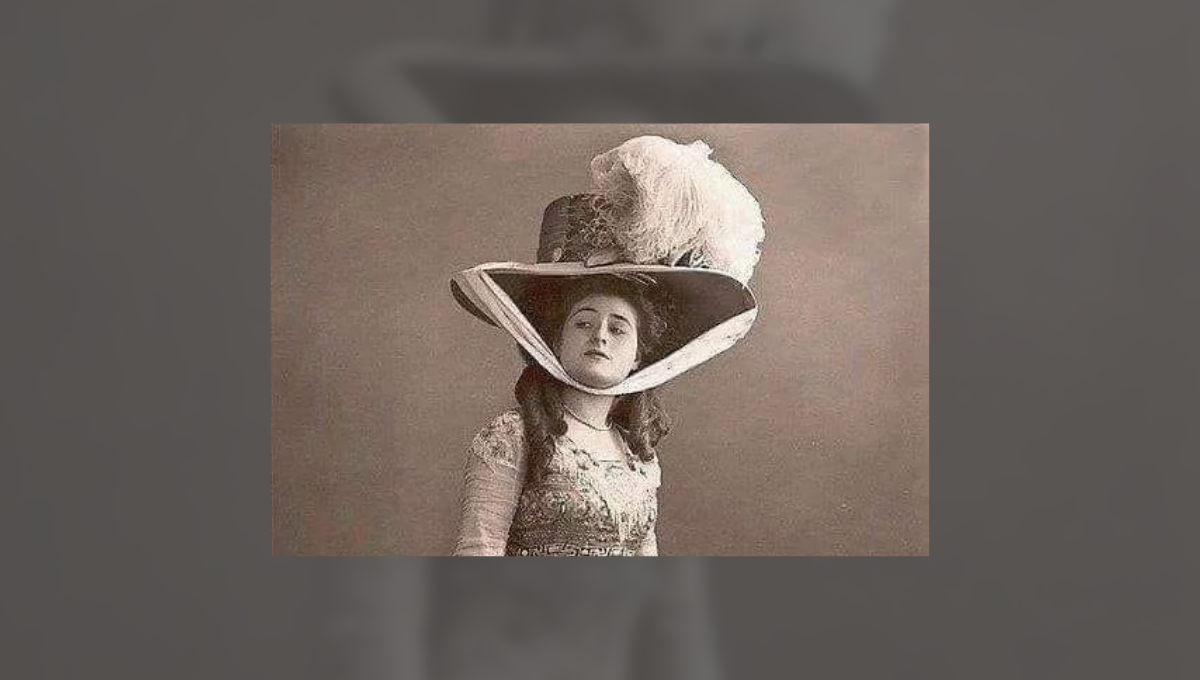

Oh, and one more thing, prior to 1880 which is just a few years before the photo of this very proud lady was taken, the age of consent for sex was set at 10 or 12 in more states, with the exception of our neighbor Delaware – where it was 7 YEARS OLD!

Feminism is NOT just for other women.

KNOW your HERstory.

A similar post on Facebook with tens of thousands of shares reported much the same in 2016 from user Lisa Bialac-Jehle.

In general, the list above accurately reports nine things that women couldn't do in 1971. We'll take a closer look at each item below:

Get a credit card in her own name

As this post explains, banks were able to discriminate against women applying for credit cards until the passage of the Equal Credit Opportunity Act in October 1974. Women could get credit cards prior to this legislation, but as The Smithsonian notes, they were likely to be asked a barrage of personal questions and were often required to be accompanied by a man to co-sign for a credit card. Even then, women often received cards with lower limits or higher rates:

Forty years ago, any woman applying for a credit card could be asked a barrage of questions: Was she married? Did she plan to have children? Many banks required single, divorced or widowed women to bring a man along with them to cosign for a credit card, and some discounted the wages of women by as much as 50 percent when calculating their credit card limits.

As women and minorities pushed for equal civil rights in various arenas, credit cards became the focus of a series of hearings in which women documented the discrimination they faced. And, finally, in 1974 — forty years ago this year — the Senate passed the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, which made it illegal to discriminate against someone based on their gender, race, religion and national origin.

Be guaranteed that they wouldn't be unceremoniously fired for getting pregnant

Women faced a number of work-related consequences for getting pregnant prior to the passage of the Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978. On the 40th anniversary of this law, the ACLU posted a statement explaining how pregnancy often resulted in pink slips for working women:

Forty years ago, working women in the United States won the legal protection to become working mothers. On Oct. 31, 1978, Congress enacted the Pregnancy Discrimination Act, making it illegal for employers to deny a woman a job — or promotion, or higher pay, or any other opportunity — because she is pregnant.

The statute had an immediate, dramatic impact on women's ability to fully participate in the workforce. Although on-the-job sex discrimination had been outlawed more than a decade earlier, pregnancy wasn't legally recognized as a type of sex discrimination. As a result, a pregnancy often resulted in a pink slip. Some employers even imposed formal policies prohibiting pregnancy outright because their female employees were expected to project a certain image — for example, flight attendants, who were expected by airlines to convey sexual availability to their businessman customers, and teachers, who were expected by school districts to project chasteness to their young pupils.

Serve on a jury

Women's road to the jury box was a long one. While the state of Utah deemed women qualified for jury duty back in 1898, it took the other 49 states several decades to reach the same conclusion. The ACLU noted that women were excluded from jury duties for a number of reasons:

Aside from the "defect of sex," women were excluded from juries for a variety of reasons: their primary obligation was to their families and children; they should be shielded from hearing the details of criminal cases, particularly those involving sex offenses; they would be too sympathetic to persons accused of crimes; and keeping male and female jurors together during long trials could be injurious to women.

While this viral posts states that it wasn't until "1973 that women could serve on juries in all 50 states," we found that this battle was still being fought for at least another two years. In 1975, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in an 8-1 decision that it was constitutionally unacceptable for states to bar women from juries.

From a 1975 article in The New York Times:

The Supreme Court ruled today that shifting economic and social patterns of the last dozen years have made it constitutionally unacceptable for states to deny women equal opportunity to serve on juries.

The 8‐to‐1 decision will have little practical effect on the make‐up of juries. All states, including Louisiana where the case originated, now have laws that do not exempt women from jury service, although women are treated differently from men in some instances involving such service.

But the majority broke important philosophical ground by acknowledging for the first time that the role of women is society was changing and that the courts must recognize their growing economic independence in assessing their legal rights.

"If it was ever the case that women were unqualified to sit on juries or were so situated that none of them should be required to perform jury service," Associate Justice Byron R. White wrote for the majority, "that time has long since passed."

Fight on the front lines

Women in the United States have been aiding military operations as nurses, cooks, and in other non-combat positions since the Revolutionary War in 1775. However, it wasn't until 1976 that the United States Military Academy at West Point accepted women to the Corps of Cadets.

Still, it would be several more years until women would find their way to the front lines. In 1994, the Pentagon restricted women from serving in "artillery, armor, infantry and other such combat roles." This ban wasn't lifted until 2013:

The US military officially lifted a ban on female soldiers serving in combat roles on Thursday and said that anyone qualified should get a chance to fight on the front lines of war regardless of their sex.

At a press conference in the Pentagon Defence Secretary Leon Panetta and General Martin Dempsey, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said that women had already proved themselves in action on America's battlefields and the move was simply a way of catching up with reality.

"Everyone is entitled to a chance," said Panetta, who is retiring form his post this year. At the moment women make up about 14% of the military's 1.4 million active members and more than 280,000 of them have done tours of duty in Iraq, Afghanistan or overseas bases where they helped support the US war effort in those countries. Indeed, some 152 women have been killed in the conflicts.

Get an Ivy League education

The Ivy League is comprised of eight universities in the northeastern part of the United States. While women were able to attend Cornell University as early as the 1870s, it wasn't until 1983 that the final Ivy League school, Columbia College, started to admit women:

The last all-male school in the Ivy League became a coeducational one yesterday when Columbia College enrolled women for the first time in its 229-year history.

It was a day of celebration at Columbia, with few alumni or students criticizing the change, and with college administrators saying the decision to admit women had resulted in the most talented freshman class ever.

Take legal action against workplace sexual harassment.

According to Time, the term "sexual harassment" was coined by a group of students at Cornell University in 1975. The term was popularized in a New York Times article published that same year, and in 1977, three court cases confirmed that a woman could take legal action against her employer for sexual harassment:

The phrase "sexual harassment" was coined in 1975, by a group of women at Cornell University. A former employee of the university, Carmita Wood, filed a claim for unemployment benefits after she resigned from her job due to unwanted touching from her supervisor. Cornell had refused Wood's request for a transfer, and denied her the benefits on the grounds that she quit for "personal reasons." Wood together with activists at the university's Human Affairs Office, formed a group called Working Women United. At a Speak Out event hosted by the group, secretaries, mailroom clerks, filmmakers, factory workers and waitresses shared their stories, revealing that the problem extended beyond the university setting. The women spoke of masturbatory displays, threats and pressure to trade sexual favors for promotions ...

... By 1977, three court cases confirmed that a woman could sue her employer for harassment under Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, using the EEOC as the vehicle for redress. The Supreme Court upheld these early cases in 1986 with Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson, which was based on the complaints of Mechelle Vinson, a bank employee whose boss intimidated her into having sex with him in vaults and basements up to fifty times. Vinson was African American, as were many of the litigants in pioneering sexual harassment cases; some historians suggest that the success of racial discrimination cases during these same years encouraged women of color to vigorously pursue their rights at work.

Decide not to have sex if her husband wanted to

This item is referring to spousal rape. The first person to be convicted of spousal rape in the U.S. was a Massachusetts bartender who broke into the home of his estranged wife in 1979 and raped her:

English common law, the source of much traditional law in the U.S., had long held that it wasn't legally possible for a man to rape his wife. It was in 1736 that Sir Matthew Hale — the same jurist who said that it was hard to prove a rape accusation from a woman whose personal life wasn't entirely "innocent," setting the standard that a woman's past sexual experiences could be used by the defense in a rape case —explained that marriage constituted permanent consent that could not be retracted.

That idea stood for centuries. Then, in 1979, a pair of cases highlighted changing legal attitudes about the concept.

Until then, most state criminal codes had rape definitions that explicitly excluded spouses. (In fact, as TIME later pointed out, it wasn't just the case that saying "no" to one's husband didn't make the act that followed rape; in addition, saying "no" to one's husband was usually grounds for him to get a divorce.) As the year opened, a man in Salem, Ore., was found not guilty of raping his wife, though they both stated that they had fought before having sex. But, even as the verdict was returned, a National Organization for Women spokesperson told TIME that "the very fact that there has been such a case" meant that change was in the air — and she was quickly proved right.

The case believed to be the first-ever American conviction for spousal rape came that fall, when a Salem, Mass., bartender drunkenly burst into the home he used to share with his estranged wife and raped her. It's not hard to see how this case was the one that made the possibility of rape between a married couple clear to the public: they were in the middle of a divorce, and the crime involved house invasion and violence. As TIME noted, several other states had also adopted laws making it possible to pursue such a case, though they had not yet been put to the test.

Even though the first conviction for spousal rape occurred during the 1970s, it wasn't until 1993 that spousal rape was officially illegal in all 50 states. While marital rape has been technically illegal in all 50 states since 1993, advocates argue that there are still legal loopholes in some states that allow for marital rape to be treated differently than rape.

Obtain health insurance at the same monetary rate as men

This item refers to the practice of "gender rating" by health insurance companies, which typically resulted in higher premiums for women seeking individual health insurance. In 2010, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Obamacare) sought to do away with the practice.

NPR reported:

Any woman who has bought health insurance on her own probably didn't find herself humming the old show tune, "I Enjoy Being a Girl." That's because more than 90 percent of individual plans charge women higher premiums than men for the same coverage, a practice known as gender rating.

Women spend $1 billion more annually on their health insurance premiums than they would if they were men because of gender rating, according to a recent report by the National Women's Law Center.

Under the health care overhaul, the practice is banned starting in 2014.

The birth control pill

This post correctly states that the FDA first approved an oral contraceptive (a birth-control pill called Enovid) in 1957. However, at the time, the pill was only approved for use as a "treatment of severe menstrual disorders," and the FDA required that it be labeled with a warning that Enovid will prevent ovulation.

A few years later in 1960, the FDA approved Enovid as a contraceptive. Still, the pill was only available to married couples. It wasn't until 1972 that birth-control pills were available to all women, regardless of marital status:

Then came the landmark date, marking the biggest change to America's contraceptive potential in history. On May 9, 1960, the FDA approved Enovid, an oral contraceptive pill released by G.D. Searle and Company. By 1965, almost 6.5 million American women were on "The Pill," the oral contraceptive's enduring vague nickname, which is thought to have stemmed from women requesting it from their doctors as discreetly as possible. That same year, the Supreme Court struck down state laws that prohibited contraception use, though only for married couples. (Unmarried people were out of luck until 1972, when birth control was deemed legal for all.)