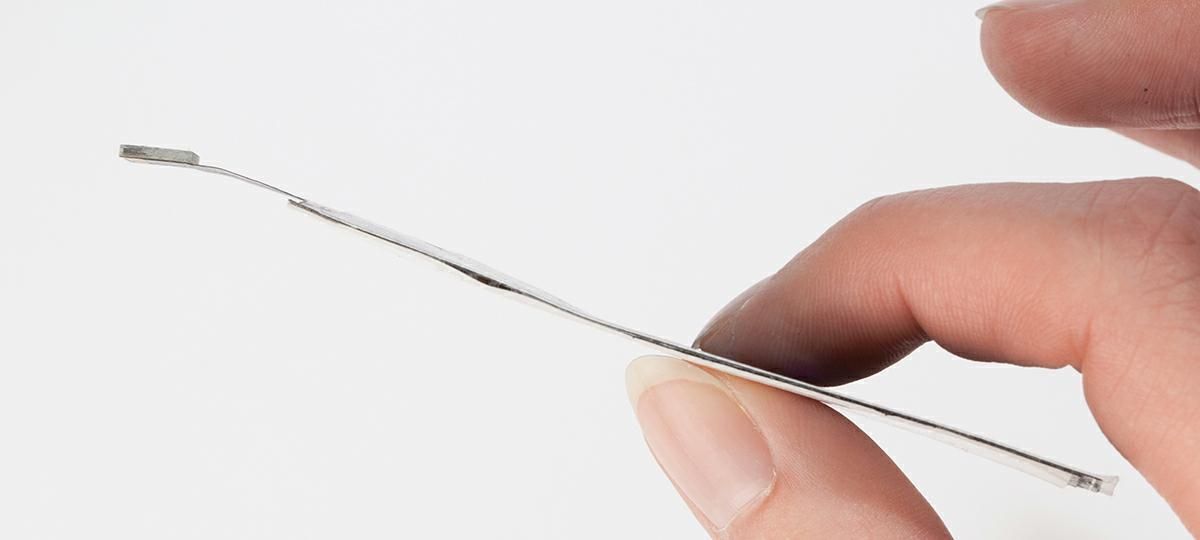

The engineering department of a defense plant at Newburgh, New York, has been experimenting with steel wire, drawing it out very fine. They finally produced a piece of

120-gauge wire — practically invisible. The boys were proud — so proud, in fact, that they cut off a strand and sent it to a rival defense plant farther upstate. "This is just to show you what we are doing in Newburgh," they wrote.Weeks went by. Recently, a package arrived at the Newburgh plant. The boys opened it with great care. Inside was a steel block; mounted on the block were two steel standards, and strung between them was the same piece of

120-gauge wire. At one end of the block was mounted a small microscope delicately focused on a certain spot on the wire. One by one the engineers placed an eye to the microscope and examined in silence the work of their rivals, who had bored, in the wire, a rather handsome little hole!

At first blush, this legend of technological one-upsmanship appears to date to around 1939, yet it is a couple of millennia older than that. As it was being told just prior to World

The courier was welcomed at the plant and given a glass of schnapps while the wire was taken to another room to be examined by German experts. Before the man had finished his drink, the box he'd brought the sample in was returned to him, now sealed with wax. "Your answer is in the box," he was told. "Please do not open it until you return to your plant."

Stateside once more, the wire was examined by the American engineers who'd slaved over it. They found a hole drilled down its center, effectively turning their solid thin wire into an impossibly-reamed hollow tube.

This pre-war incarnation reflected then-current fears of the state of German technology as America contemplated the industrial prowess of the country it knew in its heart would soon be a battlefield opponent. Sometimes Japanese technology was viewed with trepidation; another version starred them as the hole borers.

Legends often take on messages of the times. As the clouds of war darkened the pre-World

In the early 1980s, when fears about Japan's taking over the U.S. economy were running rampant, the "drilled wire" legend resurfaced in a new setting. As this version went, a American firm had produced an extremely thin glass rod and were proudly displaying this example of their company's advanced capabilities at a trade show in Texas. A group of Japanese engineers a couple of booths over asked to borrow the rod so they could examine this marvel more thoroughly. The flattered Americans handed it over. Two hours later, the rod was returned with many bows of thanks. A few days later the Americans thought to examine the item more closely and only then discovered a tiny hole had been drilled down the length of it.

Yet, as mentioned earlier, this story didn't begin as a drilled wire tale meant to help give voice to feelings of anxiety about an opponent one country was squaring off against even if that's the use it was eventually put to. The story appears in Pliny's Natural History as an anecdote involving the two renowned artists circa

Was this a true rendition of an actual event? Pliny claims the canvas (which had supposedly been exhibited as a marvel) was destroyed in a fire at Caesar's palace on the Palatine, so no evidence survives. We should also note that Pliny

In one way, the "drilled wire" story is a typical "guy tale" in which one smart fella competes with another in a peacock's show of who has the brightest feathers. In that sense, it's timeless.

Read another way, the legend exists to remind us that no matter how wonderful we think we are, there's always someone more skilled out there, and, like mama said, pride does indeed go before a fall. Especially in these days of new technology springing up in every direction, the legend's caution against ever thinking we're the cat's pajamas is direly needed, as today's complacency often becomes tomorrow's bankruptcy.

Variations:

- Who gets the better of whom varies:

- The Swiss show up the Swedes.

- Two American firms have at each other.

- German engineers prove themselves better than their American counterparts.

- Japanese engineers demonstrate themselves to be superior to Americans.

- The wire the Germans hollowed out is sent on to the Japanese, who ream it out even more, thus demonstrating themselves to be the true masters.

- One telling moves the story away from rival engineering firms and into the realm of world politics by asserting that Queen Victoria once sent a very delicate vase and extremely fine (thin) needle to the new emperor in China. By way of acknowledgement, the Son of Heaven sent back a comparable gift manufactured in China: an even more delicate vase. Inside the vase was the English needle, now completely hollowed out.

Sightings: This legend is mentioned in the 1995 Justin Scott novel, Stone Dust.