Claim: Driver who stops to pick up two hitchhikers — one dangerous-looking and the other wholesome in appearance — learns about judging books by their covers.

Example: [Brunvand, 1999]

A traveling salesman was driving from Seattle to Spokane late in the day and found himself getting sleepy. He decided to pick up a hitchhiker to keep himself awake. Just past Vantage, he saw a man with his thumb out.

The man was no sooner in the car than the salesman feared he had made a serious error. In his 40s, the man was unshaven and roughly attired, had little to say, and began looking around the car as if to see if there was anything worth stealing.

The salesman decided to pick up another hitchhiker, hoping for safety in numbers. Before he got to the town of George, he saw another man hoping for a ride and picked him up.

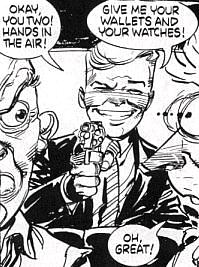

The new passenger was a clean-cut young man who looked as if he were headed back to college. The rider got into the back sear, behind the first hitchhiker in front. The salesman's relief was short-lived, however, for the car was no sooner back on the highway when the young man pulled a gun and ordered the driver to stop.

When the car was on the shoulder, the holdup man ordered the pair out of the car with a gesture of the pistol.

The gesture pointed the gun away from the front-seat occupants, and the first hitchhiker promptly dived into the back seat and knocked the young thief cold with a solid right to the jaw. The older man pocketed the pistol and relieved the

"Forty dollars," he reported to the salesman, "20 for you and 20 for me."

"No thanks," the salesman replied, happy merely to have escaped. The older man shrugged, he was now expansive and talkative.

"He's new in the business," he said of the robber. "He'll have to learn that a gun ain't a pointer. I've been in the business for

At the salesman's horrified look, the man laughed. "Oh, I ain't working today. Just headed to Spokane on a visit."1

Origins: This legend appeared in a 1983 Seattle Times column, but at least one version collected by folklorist Jan Brunvand purports to be fifty years older. Whatever its actual origins, this story has certainly been around for a

while.

English magician John Nevil Maskerlyne relates a tale similar to our legend in his 1938 book White Magic: The Story of the Maskerlynes. In his anecdote, he picks up only one hitchhiker, a rather scruffy-looking individual. A bit further down the road, he is stopped on suspicion of speeding. His guest backs his claim that he doing only the speed limit, and the pair are waved on their way unticketed. Upon arriving at the hitchhiker's destination, Maskerlyne is thanked by the hitchhiker, who then pushes two fat wallets into his hands and takes off. One of the wallets turns out to be the policeman's notebook, and the other is Maskerlynes' own bulging billfold.

Maskerlyne's account should be taken with a grain of salt. That bit about the filched policeman's notebook shows up in a 1946 round-up of tired, over-used plots. As described in that tome:

A man, motoring in New Jersey, picks up a bum who wants to go somewhere. The man — a physician — is in a hurry; he steps on the gas, moves along at sixty miles an hour. After a time, a motor-cop stops him and takes his name and address, so that he can give him a ticket. Then he tells the doctor that the man with whom he is riding is a well-known crook, just out of the penitentiary. He says some very uncomplimentary things about the bum. The doctor does not want to go to court. He is a very busy man. When he drives on, he tells the bum how he feels about wasting a lot of time. "You don't have to go to no court," the bum says. "I threw that cop's notebook away, when we reached that bridge we just passed." The bum is a pickpocket.2

Likewise, the story about the motorist, who thinks he has picked up a robber, speeding in an effort to gain a motorcycle cop's attention appears in a 1945 collection of jokes and anecdotes, that time attributed to someone named Lewis Miller, whom we are told is "the sales manager of a sizable enterprise." Just outside of Ossining, NY, Miller picks up a hitchhiker who soon afterwards tells him he's just completed a ten-year stretch for robbery in Sing Sing. Miller floors it and gets nabbed by a policeman, who writes him a ticket instead of arresting him (which had been Miller's hope). The worried businessman is instead left to drive on with the con still in the car. Upon reaching the Bronx, instead of robbing him, the passenger thanks Miller and hands over the policeman's black leather summons book.

Both

stories are of the "don't judge a book by its cover" ilk and work to drive home the lesson that people aren't always what they first appear to be, so we shouldn't be too hasty in forming firm opinions about their intentions. But of course the extra twist at the end of each tale reminds us to not drop our guard too far — in both stories, the disreputable-looking hitchhiker does indeed turn out to be all that the driver first feared even though ultimately the encounter resolves itself peaceably.

As adorable as these two related tales are, one has to wonder about them. Would a thief (even one who was "taking the day off") pass up a chance at an easy score? Probably not. Equally, it's hard to imagine a professional offering to share his take with someone who'd done nothing to earn any part of it. The salesman in the first story had simply not gotten robbed; it had been the vacationing thief who'd disabled the novice. As for the magician in the second tale, there's even less reason to reward him — the hitchhiker has already helped by getting the speeder out of a jackpot with the law. If there are any thanks to be shared in this story, they should be flowing the other way!

Barbara "half hitched" Mikkelson

Sightings: Roald Dahl tells the 1938 Maskerlyne version of the tale in his 1977 short story, "The

Last updated: 8 April 2011

Sources: |

Brunvand, Jan Harold. Curses! Broiled Again! New York: W. W. Norton, 1989. ISBN 0-393-30711-5 (pp. 108-110). 1. Brunvand, Jan Harold. Too Good To Be True. New York: W. W. Norton, 1999. ISBN 0-393-04734-2 (pp. 306-308). Cerf, Bennett. Try and Stop Me. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1945 (pp. 182-183). 2. Young, James. 101 Plots Used and Abused. Boston: The Writer, Inc., 1946 (pp. 20-21).

Also told in: |

The Big Book of Urban Legends. New York: Paradox Press, 1994. ISBN 1-56389-165-4 (p. 161).