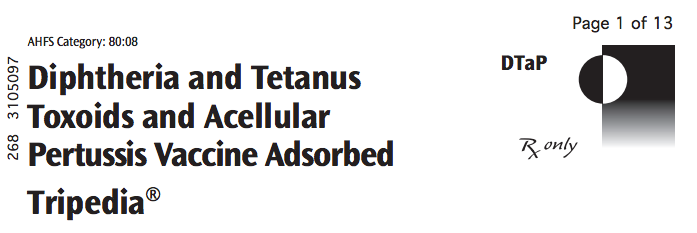

On 10 March 2016, a nondescript Wordpress blog post reporting that "autism was now disclosed and acknowledged as an adverse event reported for use of DTaP (Diphtheria, Tetanus, and acellular Pertussis) vaccine" was published by an anonymous blogger. The item primarily consisted of a sensationalist title (which suggested a new development in 2016), along with the following text and image:

There’s widespread and growing lack of confidence in the safety of vaccines ...

Know anyone who still believes that vaccines can't cause autism?

Take a look at the DTaP vaccine insert:

Predictably, it wasn't long before the blog post began popping up in anti-vaccine circles on social media under headlines such as "FDA announces vaccines cause autism" and "Now it’s official: FDA announced that vaccines are causing autism!" Readers didn't need to scan past the misleading titles to catch the thrust of the claims: The headlines insinuated that autism had recently been added to the list of known adverse affects asssociated with the DTaP, quietly confirming what science-based medical information had supposedly denied for so long.

It was true that the photograph appended to that article matched the insert available for Tripedia, Diphtheria and Tetanus Toxoids and Acellular Pertussis Vaccine Adsorbed (DTaP) as shown on the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)'s web site [PDF]:

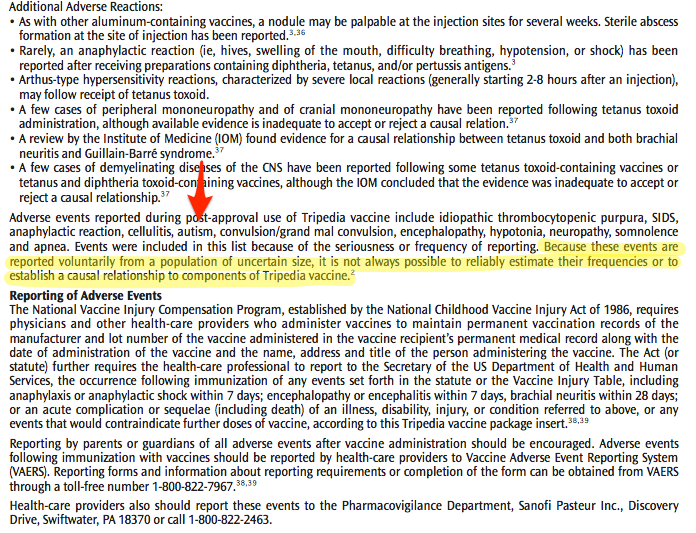

Also true was the fact that visible selective emphasis highlighted information favorable to anti-vaxxers while failing to include crucial context (namely that the listed effect was a post-approval, unverified user-reported one that does not "establish a causal relationship to components of Tripedia vaccine"):

We contacted UC Hastings law professor and immunization law expert Dorit Rubenstein Reiss about the claim, who directed us to a related passage in the Tripedia insert. While the blog highlighted Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) alongside autism as reported adverse effects, directly beneath the referenced passage was information that the rate of SIDS was lower among vaccinated infants than among unvaccinated ones:

In the German case-control study and US open-label safety study in which 14,971 infants received Tripedia vaccine, 13 deaths in Tripedia vaccine recipients were reported. Causes of deaths included seven SIDS, and one of each of the following: enteritis, Leigh Syndrome, adrenogenital syndrome, cardiac arrest, motor vehicle accident, and accidental drowning. All of these events occurred more than two weeks post immunization. The rate of SIDS observed in the German case-control study was 0.4/1,000 vaccinated infants. The rate of SIDS observed in the US open-label safety study was 0.8/1,000 vaccinated infants and the reported rate of SIDS in the US from 1985-1991 was 1.5/1,000 live births. By chance alone, some cases of SIDS can be expected to follow receipt of whole-cell pertussis DTP35 or DTaP vaccines.

Another aspect of the vaccine excerpt reproduced above was that automobile accidents and drownings were included among the causes of reported deaths that occurred after vaccination, which underscores that the nature of such statistics is an inclusive one encompassing adverse events which clearly have no causal relationship with vaccine.

Reiss also pointed us to the FDA's guidance on adverse event-related drug labeling [PDF], which states:

The ADVERSE REACTIONS section must list adverse reactions identified from domestic and foreign spontaneous reports. This listing must be separate from the listing of adverse reactions identified in clinical trials and must also be preceded by information necessary to interpret the adverse reactions. To help practitioners interpret the significance of data obtained from postmarketing spontaneous reports, the following statement, or an appropriate modification, should precede these data:

Contains Nonbinding Recommendations 8 The following adverse reactions have been identified during postapproval use of drug X. Because these reactions are reported voluntarily from a population of uncertain size, it is not always possible to reliably estimate their frequency or establish a causal relationship to drug exposure.

When we asked Reiss whether adverse event labeling included all documented reports whether or not they were linked to the drug in question, she confirmed that "the insert lists events reported even if causation evidence is sketchy. It actually says so."

Those who read down to the bottom of the eleven-page Tripedia/DTaP insert might have noticed another relevant portion:

The insert information was labeled current "as of December 2005," which first would mean its sudden "discovery" by an anonymous blogger over a decade later was of questionable (if not negligible) import. But the age of the documentation was important for a second reason: the prominent medical journal The Lancet didn't formally retract a controversial 1998 research paper which falsely advanced the belief that vaccines were linked to autism until February 2010. While that retraction was significant and definitive, twelve years passed between the paper's publication and The Lancet's disavowal of it:

A prominent British medical journal retracted a 1998 research paper that set off a sharp decline in vaccinations in Britain after the paper's lead author suggested that vaccines could cause autism.

The retraction by The Lancet is part of a reassessment that has lasted for years of the scientific methods and financial conflicts of Dr. Andrew Wakefield, who contended that his research showed that the combined measles, mumps and rubella vaccine may be unsafe.

Tom Skinner, a spokesman for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, called the retraction of Dr. Wakefield's study "significant."

"It builds on the overwhelming body of research by the world’s leading scientists that concludes there is no link between M.M.R. vaccine and autism," Mr. Skinner wrote.

A British medical panel concluded that Dr. Wakefield had been dishonest, violated basic research ethics rules and showed a "callous disregard" for the suffering of children involved in his research.

Dr. Wakefield's paper reported on his examinations of 12 children with chronic intestinal disorders who had a history of normal development followed by severe mental regressions. But an investigation by a British journalist found financial and scientific conflicts that Dr. Wakefield did not reveal in his paper. For instance, part of the costs of Dr. Wakefield’s research were paid by lawyers for parents seeking to sue vaccine makers for damages. Dr. Wakefield was also found to have patented in 1997 a measles vaccine that would succeed if the combined vaccine were withdrawn or discredited.

A 2 February 2010 article published in the British Medical Journal explained how the process of gathering accurate information to counter Wakefield's claims took years:

An academic journal is not a collection of blank pages on to which authors inscribe important scientific facts as they discover them. Rather, science is made and shaped as authors consider the declared areas of interest, impact factors, and instructions for authors of candidate journals for their work and as the papers they submit clear the successive hurdles of eligibility screening, selection of peer reviewers, responding to reviewers' comments, statistical approval, technical editing, and distribution of press releases. A graph showing first a precipitous fall in immunisation rates in the United Kingdom and then a corresponding rise in the incidence of measles was later reproduced in the broadsheets (and in at least one GCSE biology syllabus) as an iconic symbol of bad science.

That article also alluded to the immediate and lasting effects of the initial publication of Wakefield's now-discredited research:

Once the article appeared with the Lancet kitemark — cautious accompanying editorial notwithstanding — the arguments were considered by many to be proved, and the ghastly social drama of the demon vaccine took on a life of its own.

An April 2011 article in the Indian Journal of Psychiatry summarized in a timeline the havoc wreaked by Wakefield's 1998 paper, noting that a "journalistic investigation, rather than academic vigilance" led to the long-awaited retraction:

In 1998, Andrew Wakefield and 12 of his colleagues published a case series in the Lancet, which suggested that the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine may predispose to behavioral regression and pervasive developmental disorder in children. Despite the small sample size (n=12), the uncontrolled design, and the speculative nature of the conclusions, the paper received wide publicity, and MMR vaccination rates began to drop because parents were concerned about the risk of autism after vaccination.

Almost immediately afterward, epidemiological studies were conducted and published, refuting the posited link between MMR vaccination and autism. The logic that the MMR vaccine may trigger autism was also questioned because a temporal link between the two is almost predestined: both events, by design (MMR vaccine) or definition (autism), occur in early childhood.

The next episode in the saga was a short retraction of the interpretation of the original data by 10 of the 12 co-authors of the paper. According to the retraction, “no causal link was established between MMR vaccine and autism as the data were insufficient”. This was accompanied by an admission by the Lancet that Wakefield et al. had failed to disclose financial interests (e.g., Wakefield had been funded by lawyers who had been engaged by parents in lawsuits against vaccine-producing companies). However, the Lancet exonerated Wakefield and his colleagues from charges of ethical violations and scientific misconduct.

The Lancet completely retracted the Wakefield et al. paper in February 2010, admitting that several elements in the paper were incorrect, contrary to the findings of the earlier investigation. Wakefield et al. were held guilty of ethical violations (they had conducted invasive investigations on the children without obtaining the necessary ethical clearances) and scientific misrepresentation (they reported that their sampling was consecutive when, in fact, it was selective). This retraction was published as a small, anonymous paragraph in the journal, on behalf of the editors.

The final episode in the saga is the revelation that Wakefield et al. were guilty of deliberate fraud (they picked and chose data that suited their case; they falsified facts). The British Medical Journal has published a series of articles on the exposure of the fraud, which appears to have taken place for financial gain. It is a matter of concern that the exposé was a result of journalistic investigation, rather than academic vigilance followed by the institution of corrective measures. Readers may be interested to learn that the journalist on the Wakefield case, Brian Deer, had earlier reported on the false implication of thiomersal (in vaccines) in the etiology of autism. However, Deer had not played an investigative role in that report.

So while it was true autism was listed among the reported adverse events in the Tripedia/DTaP vaccine's insert, that same insert explained that all adverse events were listed, regardless of evidence of causation. Furthermore, the insert was current as of 2005, and was therefore hardly a novel finding in 2016. Five years after the Tripedia insert was printed, The Lancet formally retracted the 1998 paper to which fears about vaccines and autism were largely attributed, but by that point, the advancement of that idea had already left a palpable mark on public health in both the United States and in the UK.

However, as FDA adverse events reporting standards dictate, all adverse reports recorded in association with drugs are included in such documents, no matter how likely (or unlikely) it was that the drug had caused them.