On 30 November 2016, the Sydney Morning Herald reported on a of a class of high school boys from the Sydney Grammar School, who (as part of a collaboration with university scientists) synthesized pyrimethamine, the active ingredient in the drug Daraprim (once used as an antimalarial, now primarily used to treat toxoplasmosis and cystoisosporiasis). Daraprim gained notoriety in September 2015, when Turing Pharmaceuticals (then run by Martin Shkreli) purchased the rights to its distribution and raised its price from $13.50 a tablet to $750.00.

The Sydney Grammar School story quickly went viral, generally attached to the highly sharable narrative “Sydney schoolboys take down Martin Shkreli, the 'most hated man in the world.'” Shkreli, in series of tweets, lambasted the media for pandering to a feel-good story without looking critically into the facts.

For background, this project was conceived of by Alice Williamson, a chemist at The University of Sydney and who is part of a group of scientists that goes by the Open Source Malaria consortium. This group describes themselves as “an open source drug discovery project trying to prove that science is better and more efficient when all data and results are shared.”

An overview of that group’s work can be found in a piece at The Conversation. The group’s driving motivation is to demonstrate the utility of using an open-source, public-data, non-proprietary method to research therapeutic chemicals. In describing the concept of an earlier study they performed, Williamson stated:

The aim was to enable anyone in the community (from professors and pharmaceutical professionals, to undergraduates and school classes) to help solve our most pressing health concerns. [...]

Anyone could take part, all the data and ideas had to be public domain, and there were to be no patents. Our lab notebooks were no longer sitting on the bench of a locked lab, but were updated in real time on the internet.

In addition to this group’s scientific work, they also perform outreach and science communication activities (as many grant-funded projects do or are required to do). One such effort was the attempt to make Daraprim with high-school students on the cheap.

Because Open Source Malaria is committed to their transparency, you can read the entire fascinating thread of this project from concept to completion. Williamson first floated the idea on 8 October 2015:

One suggestion would be for the students to synthesise Daraprim (pyrimethamine) and some new analogs. This molecule has received a lot of press recently owing to the price hiking over in the USA. Turing pharmaceuticals wanted to raise the price from $13.50 to $750 per dose. Public and media outcry has led the company to reconsider the pricing options but a synthesis in the open would be great to see. Daraprim was originally synthesised as an antimalarial (by Nobel prize winner Gertrude Elion) and is now used in combination with a sulfonamide for the treatment of toxoplasmosis.

These are the main points of the story that went viral, as excerpted from the Sydney Morning News article:

A handful of year 11 students in Sydney have shown [Shkreli] up, cooking the same drug in their school lab for about $2 a dose. [...]

The students started with 17 grams of the raw material 2,4-chlorophenyl acetonitrile, also called (4-chlorophenyl)acetonitrile. You can buy it online at $36.50 for 100 grams. [...] From the 17 grams starting material, the boys produced 3.7 grams of pyrimethamine, the chemical name of Daraprim.

"That's about $US110,000 worth of the drug," Dr Williams said, based on the price mark-up of Turing Pharmaceuticals.

In a series of tweets, Shkreli argued that this analysis was misleading. His main objections with the claim were that this research proved it was possible to manufacture the drug for “$2 a dose,” suggesting that that didn’t involve lab equipment or fees, the paid salaries of knowledgeable PhDs and laboratory technicians, and that there was no oversight on the veracity of their results or its purity.

In terms of claims that the drug — based on the students’ project — could be sold for $2.00, Shkreli makes valid objections. The project (while not a full time effort) lasted roughly a year, and had the input of multiple PhD scientists, all of whom would need to be paid for their work were it not an outreach program. At many points along the way, the manufacture of pyrimethamine required repeated trial and error tests conducted by laboratory technicians.

The main hurdle, as illuminated by these discussions, was to find a way to get from their starting chemical (2,4-chlorophenyl acetonitrile) to pyramine without exposing the students to significantly dangerous chemicals or conditions. The scientists in this group did a lot of work upfront to brainstorm and test the process in an effort to identify a viable pathway.

Further, as Shkreli points out, the cost of making a batch of a drug and the cost of bringing a drug to market are very different things. If, for argument’s sake, the students wanted to get their generic version approved in the USA, they would have to subject it to a relatively shorter FDA drug trial called a Abbreviated New Drug Application which, while much less expensive, can still make it unprofitable to bring less commonly used generics to market. That was the the case with Daraprim, and it was the reason Turing Pharmaceuticals was able to hike the price without fear of being undercut.

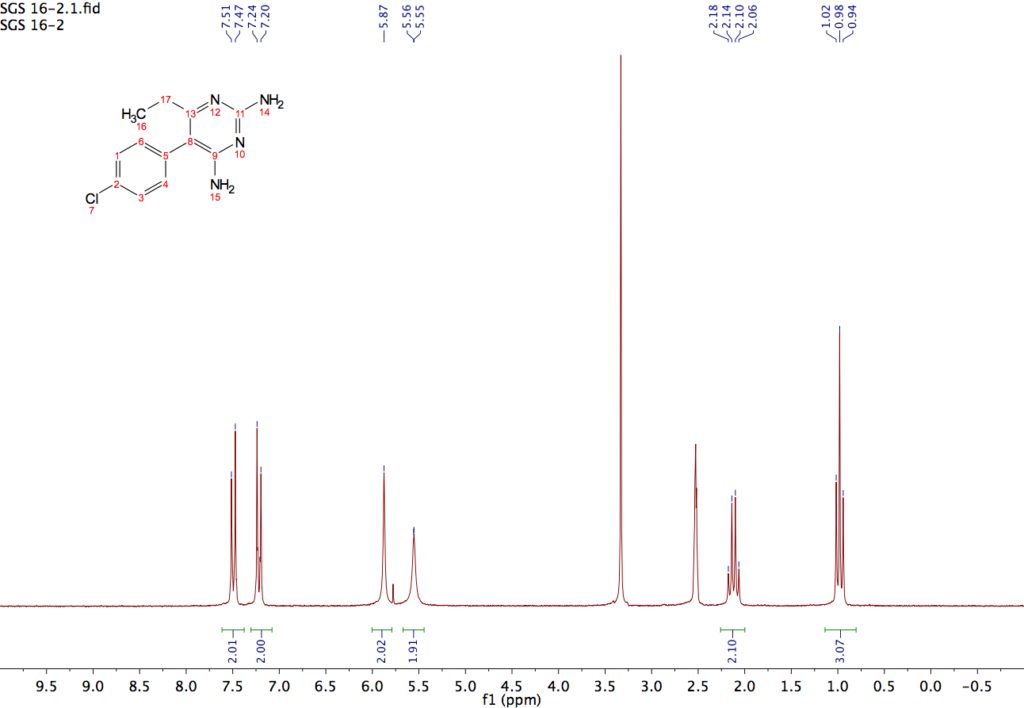

Shkreli’s last point that the trace data were not made available for critique is not fully accurate, as Dr. Williamson did post some of that data online:

No matter how much help the students had with the design and execution of this project, it is nevertheless an impressive achievement, as it is promoting discussions about the economic and regulatory environment that allow drugs that are (demonstrably) capable of being produced at a low price to be sold with such a high markup.

As a scientific development, however, the project will do nothing to destroy Turing Pharmaceuticals’ ability to set the price of Daraprim in the United States.