In September 2016, four months after a fatal dog attack, the city of Montreal, Québec announced that all pitbull-type dogs would be monitored and, eventually, banned.

Under the new bylaws, any dogs that matched the description of a pitbull type would have to be registered, spayed or neutered, microchipped, must wear a muzzle in public and be kept on a short leash, and all owners must undergo a background check at their own expense; any new ownership of the dogs would not be allowed.

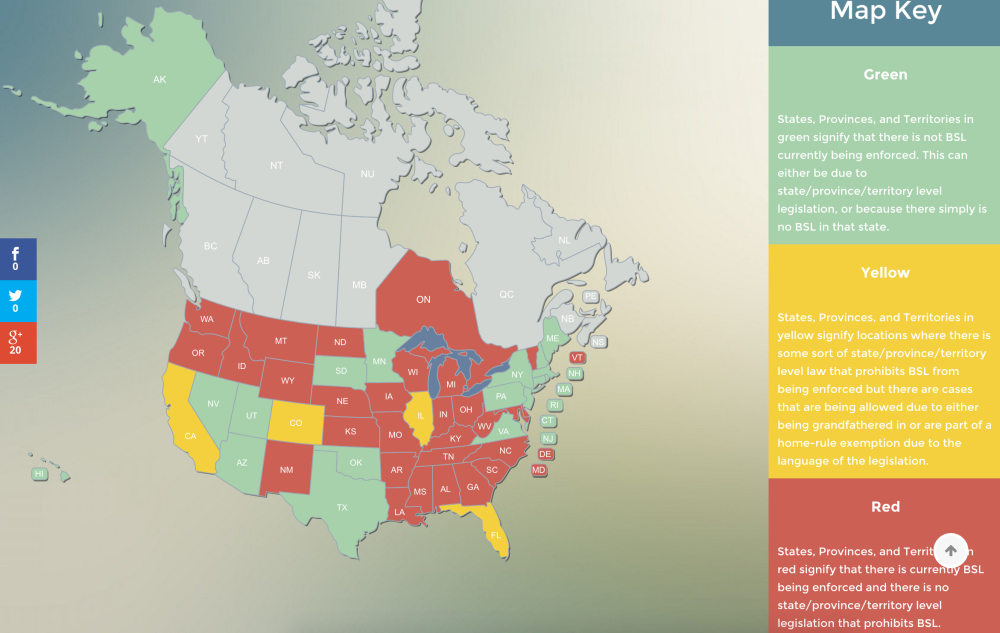

This is not the first place in Canada that breed-specific legislation (also called BSL) has been enacted (although in Montreal's case, the bylaw has been temporarily suspended following legal challenges.) The province of Ontario does not allow certain breeds of dogs, nor does the city of Winnipeg. Breed bans have also been enacted in cities throughout the United States. The web site BSLCensus.com shows at least thirty states have some kind of restriction or ban regarding specific breeds or types of dogs:

But how effective breed bans actually are across the board has been increasingly disputed as more numbers show that they do not prevent any type of attacks. In fact, bite reports tend to either stay the same or even trend upward after breed-specific legislation is enacted in a particular city or region. In Ireland, for example, the incidence of dog bites has risen by more than 50 percent since eleven breeds were banned from the country in 1998:

The Control of Dogs Regulations 1998 impose additional rules in relation to the following breeds (and strains/cross-breeds) of dog:

- American pit bull terrier

- English bull terrier

- Staffordshire bull terrier

- Bull mastiff

- Dobermann pinscher

- German shepherd (Alsatian)

- Rhodesian ridgeback

- Rottweiler

- Japanese akita

- Japanese tosa

- Bandog

The rules state that these dogs (or strains and crosses of them) must:

- Be kept on a short strong lead by a person over 16 years who is capable of controlling them

- Be muzzled whenever they are in a public place

- Wear a collar bearing the name and address of their owner at all times.

A 2015 story published in the Irish Times noted that the increased number of bites is significant even when adjusting for a larger population:

In absolute terms, the number of people hospitalised after being bitten by a dog rose from 172 in 1998 to 259 in 2013 (a rise of 51 per cent). Adjusted for population growth in the same period, the rate of such hospitalisation per 100,000 increased by 21 per cent.

There were a total of 3,164 hospitalisations in the 16-year period examined. Almost half (49 per cent) of them were patients under 10 years of age.

The Federation of Veterinarians of Europe also weighed in on breed bans:

Although some countries have adopted breed-specific measures, there is no scientific or statistic evidence to suggest that these effectively reduce the frequency or severity of injuries to people.

To date, no scientific criteria have been identified by which it can be determined that a dog is dangerous by simply describing its racial or other physical parameters.

The city of Toronto had similar results after a breed ban. In 2005, the province of Ontario moved to prohibit new ownership of pitbull-type dogs, while households that already had breeds named in the legislation were permitted to keep them, as long as the dogs were spayed or neutered and muzzled and leashed in public.

Provincial Attorney-General Michael Bryant told reporters after introducing the bill:

This is the beginning of the end of the reign of terror that pit bulls have wrought upon Ontarians for many, many years.

But it didn't quite work out as intended. The incidence of bites from pit bull-type dogs declined, of course, because there were fewer dogs of that type in the region. On paper, that might make the legislation look like an unmitigated success, until you consider that the number of dog bites changed not at all. The Toronto Humane Society noted in 2014 that the only thing that changed were the breeds of the dogs involved:

Restricting breed ownership has not reduced the incidence of dog bites. A survey of reported dog bite rates in 36 Canadian municipalities found no difference between jurisdictions with BSL and those without. Likewise, a 2010 Toronto Humane Society survey found no change in dog bites in Ontario in the years before and after Ontario’s BSL.

The organization — which, like many animal rescue groups, takes a firm stance against breed-specific legislation — pointed to Calgary, in the Canadian province of Alberta, as an example of what does work:

Calgary, however, saw a five-fold reduction over 20 years – from 10 bites per 10,000 people in 1986 to two in 2006. Rather than banning breeds, Calgary uses strong licensing and enforcement plus dog safety public education campaigns.

In the United States, breed bans have had similar results. Sioux City, Iowa enacted a complete ban on pit bulls in 2008, reducing the number of dog attacks not at all. In 2007, the year before the breed ban, 110 dog bites were reported within the county. In 2015, there were 137. The severity of the bites overall did not change:

Siouxland District Health, receives reports from the city agencies, as well as the Woodbury County Sheriff and other entities and follows up when the bite causes a break in the skin. In the agency's reports, a large percentage of the bites reported each year are listed as coming from "unknown" breeds. Breed designations are listed as they are reported to the agency.

This pattern is repeated everywhere that breed bans have been enacted and enforced, or at least places records of bites are kept. Initially, the number of dog bites do often go down, mostly because owners move, give up their pets, or have their dogs impounded or euthanized. Then (as people get dogs to replace the pets they had to give up or put down) the number of attacks levels off and then begins to rise, possibly because the breed ban creates a false sense of security: Certain breeds are banned because they are dangerous; I don't own a dangerous breed, therefore my dog won't hurt anybody.

Not every municipality keeps track of dog bites, or which breed was responsible for bites in the first place — even ones with breed bans. Further complicating the issue is the fact that it's often difficult — sometimes impossible — to tell a dog's breed by sight. What if a dog is half labrador retriever and half a breed that is classified as dangerous? Is it then only half dangerous? How much is too much of a banned breed? And how much does what a dog looks like have to do with its inherent traits?

Looking into the data on breed bans turns up an interesting finding: each region that has enacted breed-specific legislation of some sort appears to have also experienced significant, if not dramatic demographic changes over a relatively short period of time. For example, Denver, Colorado (a city that has one of the toughest breed bans in the United States — and routinely ranks among the highest in the nation in dog bites) has had breed-specific legislation in place since 1989, not long after the "energy bust" and associated migration dramatically changed the population of the city. Ditto for nearby Aurora, which put its own breed ban in place in 2005; Miami-Dade County, Florida, 1989; Yakima, Washington, 2001; Ontario, Canada, 2005; and so on.

What does one have to do with the other? The Doberman Pinscher Club of America published an article on its web site positing that it's an easy way to take action on social issues that in reality have no easy solution:

The reason that BSL and anti-dog legislation is allowed to stand and, more importantly, function as a class action suit, has a basis in the etiology of social conflict. To this end, one can find that it resonates with a certain level of public support for a simple solution. Almost everyone can recall a dog problem they have experienced and most can either tell a familiar dog story of their own or one that involved a friend. "Oh yeah, I know of a neighbor or friend who also never controlled his/her dog." Being able to tell a story about a friend or a neighbor's dog gives this kind of legislation a measure of support. Experts see it as a social problem with many parallels.

In that way, specific types of dogs become a stand-in for other, deeper problems: recessions, changing demographics, social inequality.

But the tide on breed bans is changing, with at least twenty states either not enforcing breed-specific legislation or outright prohibiting breed specific laws. These changes are coming thanks to pressure from groups like the American Bar Association (ABA), the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA), the Humane Society of the United States (HSUS), and the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA). Even the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended against breed-specific legislation in a 2000 piece about fatal dog attacks that is often cited in support of it:

Breed-specific legislation does not address the fact that a dog of any breed can become dangerous when bred or trained to be aggressive. From a scientific point of view, we are unaware of any formal evaluation of the effectiveness of breed-specific legislation in preventing fatal or nonfatal dog bites. An alternative to breed-specific legislation is to regulate individual dogs and owners on the basis of their behavior. Although it is not systematically reported, our reading of the fatal bite reports indicates that problem behaviors (of dogs and owners) have preceded attacks in a great many cases and should be sufficient evidence for preemptive action.

Each group recommends community-based approaches, such as better education about dog behavior across the board (particularly for children, who are far more likely than adults to be bitten or killed by dogs), fining individual owners with a history of negligence, spaying and neutering programs, and better reporting and data collection when a dog does bite a human.

So, after all of this, what is the most dangerous type of dog? It's complicated, but according to study after study, and when controlling for outside factors in individual dogs including training, early experiences, and excitability, the most aggressive and dangerous type of dog across the board, accountable for the vast majority of fatal attacks, is the intact male — independent of breed.